An interview with Brussels-based photographer Emmanuel Torfs

Read MoreAlbum Art

I’ve been working with London-based jazz singer Alannah for over a year, and we’ve created some memorable images together. From portraits with classic cars in the low November sunlight, to a summer night shoot in a petal-filled swimming pool, and most recently, spring on the streets of the Elephant & Castle, South London. One of the frames taken there is now featured on the cover of her latest record, Between Worlds.

This is only third time one of my photos has been used as album art, but for me, it’s always exciting to see other creatives wanting to use my work. As a photographer, I love collaborating with fellow creatives—artists, actors, performers and musicians. It offers the possibility that my photos can take on a life of their own, becoming part of their publicity, social media content, or promotional materials and with a background in printing and reprographics, I especially enjoy seeing how designers combine my images with typography and graphic elements to create posters, media posts, and covers.

Between Worlds by London based Jazz-RnB singer songwriter Alannah | 2025

Midnight Glow by London based DJ Aquaphonik | 2015

Parks by Los Angeles based Alt-Folk artist Parks | 2013

Goodbye Neopan

Fifteen years ago, when I picked up a camera again, one of the first films I bought was Fuji Neopan 400. I remembered this film from when I was a teenager and on the admittedly rare occasions I shot monotone, it was those little green boxes with the punchy black & white film that I chose

Read MoreNot for the faint-hearted

With his natural Brum charm, photographer Matt Peers captures street portraits in his home city of Birmingham as well as the rest of the United Kingdom. Armed with a smile and disarming approach Matt engages people in a relaxed and appealing way

Read MoreFilm Ferrania Stories

Some of my recent photos using the new Ferrania P33 black & white ISO 160 film were recently featured on their website page Film Ferrania Stories.

Read MoreEmotional Capture

Combining her love of portraiture and film photography Polish photographer Klaudia Nodobra exploits the beauty of the analogue process in a nascent photographic journey that, for me, truly penetrates and compliments her creative vision.

Read MoreReview of the CONTAX 645

Six months ago I changed cameras. Deciding that I needed a new medium format camera was for me, both a difficult and easy choice.

Read MoreA Sense of Mystery

Shifting beautifully between refined portraiture and fragments of landscapes, Greek photographer George Kamelakis translates a deeper sense of emotion through his camera. Going beyond the conventional to explore connections and detail, he uses light, shadow and colour to portray people and places, often merging them to unique effect.

Read MoreThe Last Picture Show

Raised in Fargo, North Dakota and having lived in Canada and Scotland photographer Jennifer Jean only took up creative photography in the last ten years. Now living in rural Texas, she captures the quiet corners of the small towns that surround her.

Read MoreSeeing and working with the Nikon Coolscan

“But first how do I plug it in?” That’s the cheeky question I ended my last post with and of course, that bit is easy but what is not so straightforward is how to connect an old Coolscan to a modern computer.

Read MoreContax iiia Review

Review of a 1950s Icon

Regular readers of this blog will remember reading Australian photographer Dom Ruikeh’s review of his CONTAX RX. So, last year when I discovered that he also had a Contax iiia I was quick to ask for a second write up of this iconic camera of the 1950s.

This is a review of the Zeiss Ikon Contax iiia which is one of the most beautiful classic cameras to look at, to hold, and to use. It is the same camera as the Contax iia, but with a lightmeter.

HISTORY

The Contax iia & iiia were produced between 1950-1961 in Stuttgart, West Germany by the Zeiss Ikon AG company. By the time of their introduction, the Contax name was already well regarded due to its predecessor - the Contax ii which was the 35mm camera of choice for professionals such as Robert Capa and only really rivaled by the Leica III series.

Appearance

It is a great feeling to look at and admire a shiny Contax iiia. Of all my cameras, no other has as much surface area metal, which adds to its jewel-like status. Even compared to my Leica barnacks, the type of chrome used in the Contax appear much brighter and shinier.

At 635g without a lens it has a fair bit of weight to it, reminding me that this is a serious luxury instrument that was built to last. There are no rubber or plastics that will degrade or get sticky over time. It is predominantly metal, including the shutter curtains that are aluminum and capable of achieving speeds up to 1/1250s which was the fastest of any camera of the time and not surpassed for decades to come. The only non-metal parts are the leather covering, the glass finders, and the nylon strings to tension the metal shutter curtains.

The Contax iiia has an exposure meter built into its top plate, which noticeably increases the height and weight of the camera compared with the Contax iia which has no exposure meter and weighs only 510g. The lid will spring open upon pressing a knob which allows light to activate the selenium photocells. Amazingly the exposure meter on my camera still works and is accurate!

In Use

Whilst the Contax iiia looks good enough to just sit in a display cabinet and admire while sipping whisky, it is a sophisticated working instrument even for today’s standards. The camera has three unique features which is why I use the camera today:

Focus adjustments can be made by turning the focus wheel with the right hand index finger

Additional focus wheel. Whilst you can focus the lens the traditional method by turning the lens barrel with your left hand, the Contax also has a unique focus wheel beside the shutter release button. This allows you to focus, compose, and release the shutter all with the one hand. The other benefit of the additional focus wheel is when changing the aperture. I often use my right index finger to lock the focus wheel in place so that the lens does not turn when changing aperture.

Contax iiia alongside the Sonnar 5cm f1.5 lens

Internal helicoid for 50mm Zeiss Sonnar Lens. Let’s be frank here - as good as a camera is, it is the quality of the lens that is of more importance in the output and look of the photo. The original German made Zeiss Sonnar 5cm f1.5 lens in my opinion is the greatest lens for portraits ever made, and the native camera to mount this lens are the Contax rangefinders. (As this is not a lens review, you can read about the many extols of this lens by other online reviewers). This lens mount is known as the Contax Rangefinder (RF) mount and there are not many camera options to mount this (see below on ‘Alternatives’ section) which is a key reason for using the Contax iiia today.

You will note as well the Sonnar lens has no focusing mechanism. Instead the focusing helicoid is built inside the Contax body. This allows almost half the length of the Sonnar lens to sit discreetly inside the camera body, making this combination a very compact and slim camera. The photo below compares the width profile of the Contax iiia and Sonnar lens vs the Leica III and Elmar lens. The Elmar 50mm f3.5 is the smallest of Leica 50mm lenses yet is comparable in size to the Sonnar when mounted and extended. Considering that the Sonnar is a f1.5 and the Elmar is a f3.5, this is an impressive feat of the Zeiss design.

Contax iiia on the left, Leica III on the right

Reloadable film cassettes. Another thoughtful design feature of the Contax iia & iiia are the reloadable cassettes which can be used on both the film-feeding side, as well as the take-up spool side. Other cameras allow for reloadable cassettes to only insert on the film-feeding side of the camera (eg. Leica’s FILCA) which means they are only used for bulk film loading. The Contax however can also be used on the take-up spool, meaning there is no need to rewind the film once you’ve finished the roll, minimising the risk of dust or scratches on the film. You simply remove the back, and take out the Contax reloadable cassette which is scratch proof and light-tight. There is no need to trim the film leader to a specific shape or fumble around trying to take the leader out of a 35mm film canister.

Contax reloadable film cassette

Things to watch out for:

I have owned three Contax iia’s and three Contax iiia’s but have since consolidated my collection to just the 1 mint condition Contax iiia as pictured in this review. Things to look out for include:

Leather covering - the infamous Zeiss bumps were present on all my cameras. This occurs over time when the copper rivets on the camera body react with adhesives in the leather covering. Zeiss bumps are very easy to remove and fix permanently. There are several online forums which detail how to do this which you can look up, or feel free to leave a comment below and I can detail how I did mine.

Glass viewfinder and rangefinder – dusty and hazy viewfinders/rangefinders are common, and the downside of the additional focus wheel detailed above means that there is a small gap in the body for dust and moisture to get into the rangefinder. Again there are several online forums and videos that detail how to clean this on your own. Patience and the right tools are needed, and be careful when reassembling the front plate to ensure the rangefinder is not misaligned. It is a pain to re-calibrate this accurately. If this has happened to you leave me a comment and I can detail how I calibrate the rangefinder.

Alternatives

There are very few options when it comes to mounting Contax RF mount lenses, which makes the Contax rangefinders still appealing today. The only alternatives I am aware of are:

1. Voigtlander Bessa R2C- this was a limited special production run by the Cosina Co. in Japan to equip the Contax RF mounts in their Bessa rangefinders. They are very rare and command ridiculous prices on the second hand market, even if you can find one. It practically does everything the Contax iiia does, but better and faster. I love using the modern Bessa R2C as it takes me half the time to take the same photos as the Contax iiia. The longevity of the Bessa however is questionable, with many parts made of plastic and the rubber grip on mine starting to degrade and feel sticky. If I can liken the Bessa R2C to a sleek and efficient modern Honda, the Contax iiia would be a classic luxury Mercedes (also made in Stuttgart) which can be passed down to future generations.

The Contax iiia on the left, compared with the Bessa R2C on the right

2. Kiev– the Soviet made Kiev cameras are direct replicas of the Contax cameras. I have not used any of these but understand the earlier models after the second world war were not simply copies, but actual descendants of the Contax cameras, with many technicians and manufacturing equipment moved from Germany to the Soviet plant in Kiev, Ukraine. These are plentiful on the secondhand market but the postage to Australia is often more than the camera itself.

3. Contax RF to Leica adapters – the final option is to purchase an adapter to fit onto Leica LTM or M cameras. As these adapters require built-in helicoids they are not cheap, with good ones made by Amedeo, Kipon, or Yeenon going for US$300 and upwards.

Here are some sample photos taken on the Contax IIIa

Thank you Dom for this excellent review, for me it’s fantastic to see passionate photographers still treasuring, maintaining and using vintage cameras like the Contax iiia.

Dom Ruikeh is an award winning Adelaide and Sydney based creative that goes by the name Refracting Light. He uses a variety of media particularly 35mm film which he bulk rolls, self-develops and scans. His main focus is raw, natural-style portrait photography. He is also a camera collector and restorer with a particular fondness for all things Zeiss. You can see more of his work on his website or on his Instagram gallery @refracting_light

© All Rights Reserved | Dom Ruikeh 2023

Memories of the 1957 British Grand Prix

PERSONAL DOCUMENTARY & KODAK KODACHROME

Recently I was out with my friend Charles Evans shooting his lovely Citröen DS and in a welcome distraction from the sheer beauty of focusing on the car, he asked me if I was able to scan Kodak Kodachrome? Well as it happens I am. Scanning Kodachrome is not straightforward and my scanning software has built-in profiles made specifically for Kodaks most famous colour film stock.

A couple of days later Charles dropped off some boxes of slides taken by his father for me to scan. Spreading them out over my lightbox I could see many potential gems, but it was the distinct colours of Kodachrome that initially got me excited. Kodak introduced Kodachrome in the mid-30s and until its demise 70 years later, it was considered to be one of the most beautiful film stocks ever. Kodachrome was used in still and motion picture photography and with its signature colours was the colour film of choice of professional photographers in an era when black & white dominated. Kodachrome was a complex film and required its own processing chemistry, in fact, it was sold process-paid, once shot it was sent back to Kodak’s network of labs for developing.

Charles seems to remember that his father used a Contaflex camera. I use a CONTAX camera for 35mm too so I was really happy to be starting this small project. As I began to scan and process the slides, I could see through the photos the passion of the man who took them, they were a record of his days out at the Grand Prix, car shows and photos of his wife and friends, the sort of personal documentary that many of us record every day. Except over time these photos have slowly become more than just personal, they have become history.

Amongst all the slides one caught my eye. This beautiful photo of four Maserati 250F’s lined up at the beginning of the 1957 British Grand Prix at Aintree. I love everything about it, the unmistakable colours of Kodachrome that almost transport any viewer directly back to the late 1950s. The Italian racing red of the Maserati cars is mesmerising set against the muted greys and browns of the track. Yet there are beautiful pinches of colour all over the frame. The skin tones of the participants, the light blue overalls of the mechanics and the small but distinctive yellow Autocar advertising sign in the background all contributed to the feast. Finally the cooling tower and smoke stacks oppressed by the cold grey north western sky, a solid reminder that this is not Monaco or Monza. What a priceless piece of history. Thanks Mr Evans.

Photo Credit: Kodachrome sides on blog list page by Jo Gala

What Next - Scanning and the Coolscan 8000

Part I - Update and introduction to the

Nikon Super Coolscan 8000 ED

It’s been a while since I wrote about scanning. I’ve documented my own decade-old scanning journey on this blog because this bewildering and essential part of photography is endlessly interesting to me and because I want to contribute to the shared experience of other photographers out there. I guess, like most people, when I first started scanning I turned to the internet for knowledge and know-how, so now why not add my own? What I have written here and previously has never really been for the experienced photographer who knows all about scanning, it’s more really for anybody starting out and considering getting into scanning.

For sure, scanning can be baffling and I don’t blame any photographer who delegates it to a professional lab. It’s time-consuming, expensive with a frustratingly steep learning curve, but ultimately for me, it was and remains one of the most essential parts of my photographic experience. As a modern film photographer who shoots hybrid analogue, it is the scanner that bridges the gap. I believe that 90% of the visual beauty and charm of analogue photography resides in the film negative. The look and feel that we all love so much is embedded in the emulsion of the films we use. Recovering this is the job of the scanner. These are the machines that translate the images on film into the digital domain and allow all the modern advantages of colour correction, post-processing and sharing of the finished photos onto the digital world of screens, websites and social media.

Not everything is rosy and ideal with this hybrid workflow, because of the dominance of digital screen presentation the photograph sadly, in its most beautiful form as a print has declined, but that’s another story and not one that the scanner is responsible for. After all scanned film photos can be printed and hung on a wall as effectively as any darkroom print.

That original lab scan from 2012, that got me thinking could I do better?

Anyway, back to scanning and scanners. My journey started back in 2012 when I got back a roll of Kodak Ektar 100 developed and scanned by a lab. On the roll there was a portrait, I could see immediately that the photo had potential, that feeling you get when you see a photo for the first time and know that the picture you had in your viewfinder and more importantly in your mind was there on the screen. But sadly for me although the composition, pose and expression was there and even the focus and exposure was good, the scan was terrible. No amount of colour correction, post-processing and adjustments in Photoshop was going to save this photo. I was so disappointed. Looking at the frame on the negative it looked good, not dark or light or strange in any way. It must have been the scan. I must have had an operator who was having a bad day, distracted or not bothered and so the resulting TIFF was simply awful. It was not the first time this had happened and I decided to change lab, but not before exploring the possibility of buying my own scanner. So in a moment of technical confidence or ignorant naivety, I decided that I wanted to be the master of my own photographic future and bought an Epson Perfection V500. An entry-level flatbed scanner to scan my own 35mm and 120 films. Although I have more than once come very close to regretting becoming a scanner owner the reality is I have slowly, over time, mostly enjoyed the challenge, learning a lot along the way.

There are lots of ways to digitise film, from the simplest mobile phone application to high tech drum scanners. On the internet, there is no shortage of advice, tutorials and opinions, including my own pronouncements on the subject. But what there isn’t is a large choice of scanners or the software necessary to drive and invert the scans. The zenith of non-lab scanning was over 20 years ago when professional photographers were converting from film to digital and the commercial need existed for high-quality desktop scanners at accessible prices for professional and amateur use. Dedicated machines made by manufacturers like Minolta, Canon and Nikon were all capable of producing excellent scans that were practically as good as the scans by pro labs. Fast-forward 20 years and the options are much more limited. Epson continues to manufacture their Perfection flatbed series and there are dedicated scanning options from a handful of manufactures like Plustek and Reflecta. An alternative and increasingly popular way to digitise film is DSLR ‘scanning’. By setting up a digital camera fitted with a macro lens to photograph a negative over a light source. Many new film photographers come to shoot analogue via digital and already have very good digital cameras so this is a great way to exploit the equipment they already own to digitise film. It’s quick, if you don’t count the amount of time spent cleaning spots and dust in post and convenient if you don’t mind a miniature oil rig sitting on your desktop. Photographing the film produces very sharp images that are in RAW format and so can be handled in any modern workflow.

The not so perfect ColorPerfect Photoshop plugin. For me at least!

Speaking of which, as well as a shortage of contemporary scanners there isn’t much choice of software to control them either. If a scanners primary job is to hold a negative flat in its holder so that it can be focused on to achieve sharpness, while the transports stepping motor and lens scan the film, then the software that drives it completes the second important phase. The inversion and accompanying processing controls that allow for colour and tonal correction before output. If you’re using an Epson machine it comes with EpsonScan, a basic but competent software that works and until very recently I still used it for black & white. Other than that there are two choices. SilverFast and VueScan. Both products have been around for a long time, both have their fans and detractors. I’m not going into what they are all about here, there’s plenty of information on the web about each of them. I’ve used them both and through gritted teeth over the last 3 years opted to scan on SilverFast. It’s an ugly place to be but it produces good results and that’s what matters, that and not speaking to the company who make it, LaserSoft imaging, which is almost always an unsatisfactory experience. If you can’t tolerate the confusing interface of SilverFast or the rudimentary boxes of VueScan then you can spend less time in them and produce linear scans as DNG’s or confusingly in the case of SilverFast HDRi. That’s High Dynamic Range ain’t it? No, it’s a SilverFast’s RAW scan! With all the controls of the software turned off the scanner creates a pure scan with no influence from the scanning software, a negative scan produced like this still has its orange base it is scanned as a positive. With these types of scans, there are many ways to invert them. You can use Photoshop, Adobe Camera Raw, Lightroom or probably any other photo editing software. Inversions done like this are far from automatic and require a fair amount of colour knowledge to build the contrast and colour tones from the initial washed out presentation. An alternative to manual inversion is the Lightroom plugin Negative Lab Pro, more about that in a moment, and the Photoshop plugin ColorPerfect. ColorPerfect like SilverFast is neither intuitive nor attractive. I used it for some time and found it frustrating and not so perfect. It gave me inconsistent results and in the end, I gave up on it. I do know some photographers who swear by it, but it’s not for me. Negative Lab Pro is the popular and game-changing Lightroom plugin that has allowed the whole DSLR ‘scanning’ scene to flourish. It was designed to take advantage of RAW files created by digital cameras and the RAW workflow offered by Lightroom. In its second updated release, NLP supported DNG liner scans and so became practical and useful to scanner users as well. I have tried NLP on several occasions, the inversions made by this plugin are very good. Colours and tones are generally great from the moment of conversion and the plugin offers a range of simple to use colour controls in a nice pop-up user interface. I can see why this software is rightly popular but it has never become a part of my scanning process. Not because of its inversion and image quality but because I could not live with the convoluted workflow, it just wasn’t for me. Having said that, I honestly think that anyone starting out scanning should investigate Negative Lab Pro.

Back to my scanning story, after 5 years using my Epson V500 I upgraded to a V800. The difference between an entry-level flatbed and the very best flatbed was enormous. I was happy and dived into rescanning my entire archive. Although Epson flatbed scanners have no way to focus on the film the company have developed over the years scanning frames that are height adjustable, whereby you can fine-tune the focus for optimum sharpness. Film flatness is also a critical part of any scanning and there was some improvement here also but it was somewhat limited in the case of 35mm strips, really curved film never sits that flat in the Epson holders. For 120 I bought an aftermarket holder from a company called Betterscanning.com. This is a brilliant product and if you use a flatbed and can get hold of one, do not hesitate. The frame has anti-newton glass to keep the film strip flat and has infinitely adjustable nylon screws to fine-tune the focus height above the scanner lens. Brilliant, just a shame they no longer appear to be available. Having and using the Epson V800 was always a good and practical way to scan film, but I knew there was a better way to scan and always dreamed of a dedicated turn of the century scanner. A Coolscan of course.

This summer I managed to get my hands on a beautiful Nikon Super Coolscan 8000 ED. The 8000 was Nikon’s first combined 35mm and 120 film scanner and was manufactured between 2001 and 2004 when it was superseded by the in-demand Coolscan 9000, their last combined format machine before they left the market completely in 2008. My unit is in very good condition for a 20 year old machine, recently having its mirror cleaned and a full CLA (clean, lubricate and adjust) by a specialist, a good find, I hope. I looked for an 8000 because and anyone who knows about the 9000 will know that they fetch extraordinary figures. The 8000 is very good value by comparison. There are differences and I’m sure the 9000 is better being quicker, quieter with apparently improved shadow detail but the 8000 is ostensibly the same machine but at a third of the price. The question I had to ask myself is paying three times more worth that? Not for me, it wasn’t. But the real question is a dedicated 20 year old machine better than what I’ve been using for the last 4 years? But first, how do I plug it in?

CONTAX RX Review

When my friend, Sydney based photographer Dom Ruikeh aka Refracting Light Photography, told me he was searching for a CONTAX RX of course, I was immediately interested in what he could find. Looking for and finding a good used camera is always an adventure and sure enough Dom's new RX was just that. It was such an experience that I asked Dom if he would like to write about it and show off some of the first shots taken with this brilliant 90s camera.

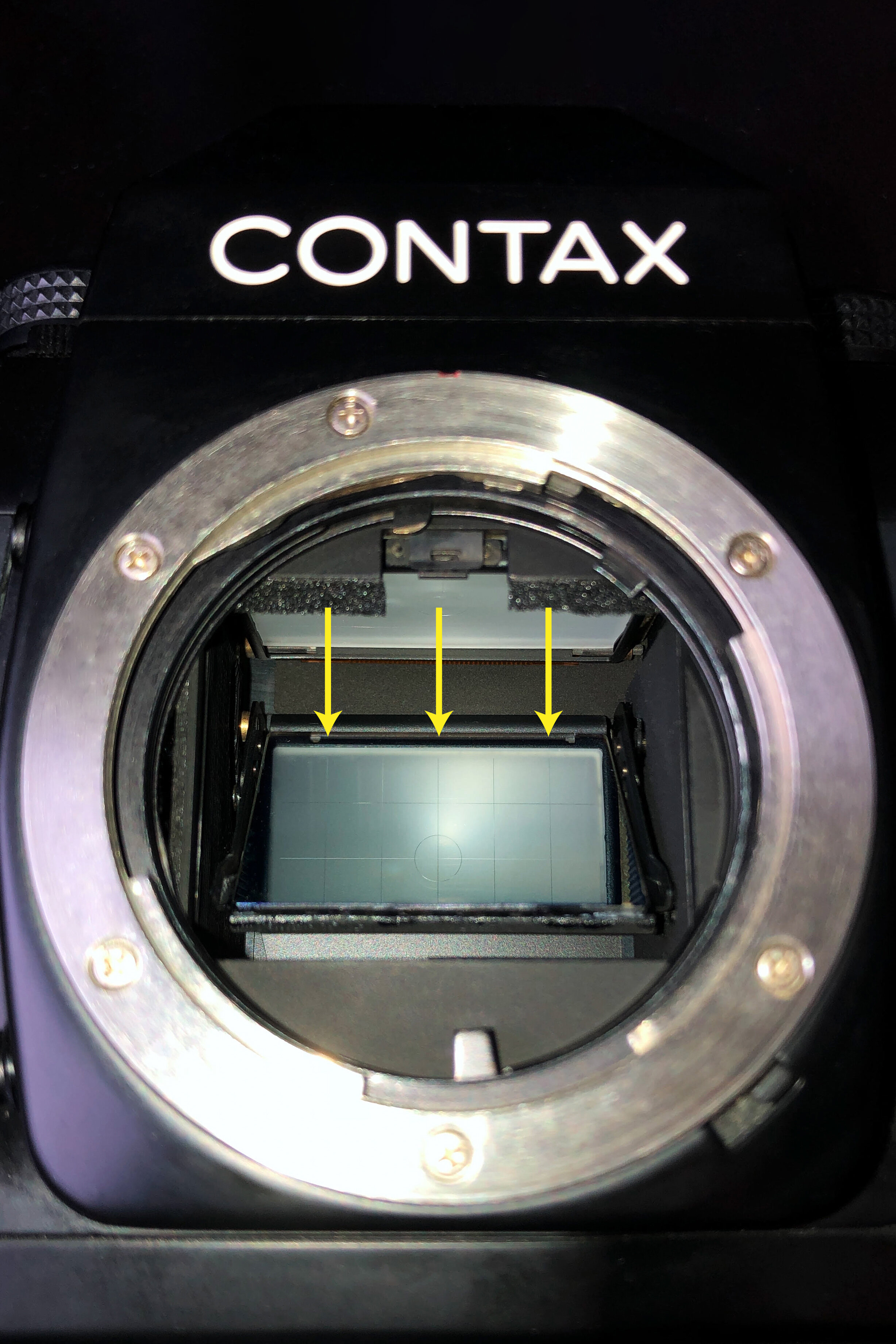

CONTAX RX Review and fixing the CONTAX mirror-slip issue

By Dom Ruikeh

I have been a long time collector and restorer of Minolta, Mamiya, and M42 cameras and lenses, but six months ago I began delving into the world of CONTAX as a means to use Carl Zeiss glass. Now six months on, I find myself downsizing my collection to fund my growing investment in the CONTAX system. My newest addition is the CONTAX RX, these are my initial impressions of the camera and how I fixed the mirror-slip issue that came with it.

I had been following the prices of the CONTAX RX for a while and when I saw a great deal on a ‘mint’ condition RX on eBay Japan, I pulled the trigger and bought myself an ‘early birthday present’ five months early in fact! but it was my way of rationalizing the purchase to my wife. The camera arrived with record speed and it indeed looked mint, however, my excitement was short-lived when I noted the mirror was not fully opening when the shutter was released. I wrote to the seller about the problem and was pleasantly surprised when they apologized and promptly refunded me the full cost of the camera AND let me keep it to try fix on my own. My birthday present just got a lot sweeter! So before I get into the actual review of the camera, I’ll take a little detour to explain how I fixed what I discovered to be known as the ‘mirror-slip issue’ which can occur in various CONTAX SLR models particularly those manufactured in the 90s.

Fixing the Mirror-Slip Issue

With all the brilliant technology and engineering that went into building these cameras, it was unfortunate that a simple weak link in the production has caused these amazing machines to require this repair. That weak link is the adhesive that was used to fasten the mirror to the camera. Over time, particularly in environments of heat and humidity, the adhesive begins to lose its bond causing the mirror to slip down.

So after spending a few nights researching every repair forum, operating manual, and YouTube video I could find, I discovered there are generally two methods that others have used to try to fix the problem.

The first method involves heating the mirror with a blow-dryer then gently nudging the mirror back into place. This however appears to be a temporary fix, with several users commenting that the mirror slid back down after a few months. In order to make this fix more permanent some have applied sealant or glue to the top part of where the mirror sits flush with the carrier plate, however, there are some reports of the sealant seeping in between the mirror and plate causing discoloration or blotting resulting in dark patches seen through the viewfinder.

The second method involves a razor blade to get under the mirror and cut it from its carrier, then after using a solvent to clean and remove the existing adhesive, reattaching the mirror with double-sided tape. This appears to be the more permanent fix solution, though there is some risk of breaking the mirror.

I had originally decided to use the second method until I read some reports that the electronic focus confirmation of the RX no longer worked after the fix. As the focus confirmation is a key feature of the RX, that risk was enough for me to try another solution. I ended up using my own hybrid solution by first applying a very thin layer of 3M adhesive transfer tape to an area at the back of where the mirror will eventually sit. Then I engaged the bulb setting, keeping the mirror open whilst using a blow-dryer on its highest setting to heat the back of the carrier plate. It took less than 20 seconds of heating for the existing adhesive to become loose enough for me to nudge the mirror all the way up until it hit the back-stop of the mirror support plate, where I had previously placed the adhesive transfer tape. Repair done, I was ready to test my new camera.

Using the CONTAX RX

In 1994, when Nirvana and Radiohead were dominating radio playlists and Forrest Gump was cleaning up at the Oscars, on the other side of the world, in Japan, the CONTAX RX was born. The RX was marketed as the more advanced higher-end version of the 167MT, and it sat below the RTS III model which was marketed to professionals. The RX was one of the last CONTAX SLR models produced by Kyocera, before the company focused more on developing their medium format cameras.

My immediate impression of the camera is how well it sits in my hand. Yes, it’s a chunky beast, and though the spec sheets show the RX is 810g even without battery, the weight is perfectly distributed and has a nice protruding grip which allows me to carry it confidently with one hand. I can’t say the same for the RTS which although is a lot lighter than the RX, feels like it will slip off if I carry it with one hand. The RX however is certainly not a discreet camera and not one I would use for candid street photography, for that I prefer the RTS with Tessar. If I can liken the RTS to a Porsche 911, with its sleek polished lines and compact body. The RX would be the more angular, bigger and heavier Porsche Macan SUV.

The viewfinder is big with 95% coverage and 0.8x magnification. It has a true pentaprism, not pentamirror, for optimal brightness. The simple layout of the dials and buttons are well thought through, and the viewfinder has all the information you need without moving your eye away to make adjustments.

A unique feature of the RX is its DFI or Digital Focus Indicator, an electronic focus confirmation system which visually confirms in the viewfinder the depth of field for your chosen aperture, as well as whether your centre subject is in focus. An easy to read series of electronic dots confirm focus. If the dots are to the left of the centre it's letting you know that you are back-focused. If the electronic dots are to the right of the centre it is letting you know you are forward-focused. My experience thus far is that whilst the focus confirmation is accurate, it is a tad too slow for my style of photography. I mainly shoot portraits and fashion editorials so the approximate 1-2 second lag for the focus confirmation to register is too long. I can see the feature being particularly useful for still life, macro, and product photography though.

Another interesting feature is the data back which prints the time or date in between the frames rather than on the image itself. Perhaps though even Kyocera did not predict the longevity of their cameras because the data-back's date only goes up to 31 December 2019!

Overall, I can see myself using the RX frequently as part of my regular rotation of cameras. The biggest pluses for me are the ergonomics, the bright viewfinder, and of course the ability to natively use Carl Zeiss glass, particularly the heavier lenses which are so well balanced. I would not hesitate to use this on my next professional photoshoot. For long walks or street photography, however, I would leave it at home opting for something smaller and lighter.

Thanks Dom. As I said it has been a bit of a challenge but I'm certain he will enjoy using this camera for many years and hopefully that mirror will stay right where he fixed it. You can see more of Dom's work and follow him on Instagram at refracting_light or on his website at www.refracting-light.com

© All Rights Reserved | Dom Ruikeh 2021

In Conversation with Thomas Berlin

Recently, I had the pleasure of talking to German photographer and blogger Thomas Berlin. It’s quite something to have my interview featured alongside some really great fellow photographers on his website. He asked me some challenging questions about my photography that required me to think carefully about what and why I shoot the way I do, something that was both engrossing and insightful.

You can check out his interview series as well as see Thomas Berlin’s own work at www.thomasberlin.net

Unseen Connections

an interview with Mark Forbes

Some years ago I came across a photo of a smashed car wedged between two huge converging walls of concrete. I was immediately arrested by this photo's content, light and colour and its sense of destructive beauty. Like the tightly squeezed car, crammed into this single frame was so much potential story. How? Where? Why? Of course, from that moment I had to follow and see more from its photographer.

Based in Melbourne, Mark Forbes shoots quiet scenes of the everyday in a documentary style where urban corners and vistas are framed and composed in such a way to as to bring a striking beauty to the familiar and mundane. So after years of looking at his pictures, I thought now might be a good time to ask him about his work and photographic influences.

• Mark, can you tell me a little about yourself?

Hi Tom, thanks for having me on board for this interview. Sure, so I was born in Middlesbrough, England to Scottish parents and spent some of my childhood in England, some in Sydney, some in the Netherlands and the last few years of my high school were in Melbourne. As a family we did a lot of travelling at all ages, moving from country to country and often only living in one place for a few years at a time, before moving again. One of my favourite memories as a child was being in airports and on planes travelling from place to place. It was like we were always going somewhere new and mysterious. I’ve definitely taken this love of travel through to my adulthood.

• How and where did you discover photography?

My dad had a picture he took from a sailing boat in Sydney harbour enlarged and hung on the wall. That really is my first memory of any photograph. The first time I have any vivid recollection of taking pictures myself is when I was at school in the Netherlands in year 10 (15 years old) and we were leaving to move to Sydney. Usually we were not allowed to bring cameras to school, but as I was moving I snuck in a little film point and shoot (it could have been a disposable) to take photos of my friends in my last days there. So it was really all about taking pictures to not want to forget things - which at the simplest level is I think why many photos are taken. After that I really don’t remember much about photography in my life until after leaving university and buying a film SLR at the airport to go on a trip to Europe.

• How does photography work for you as a creative form?

It works for me at in the most basic sense in terms of being a way to communicate visually with other people the things that I see on a day to day basis. When I approach a scene I tend to find that there is really only generally one way that I think it looks the most interesting or the way that I want to capture it - often this is a view that comes very quickly. I get a sense of peace and calmness when I photograph, and also a deep sense of enjoyment. It’s like time can be irrelevant often and you are really able to zone into something that consumes you. You can forget all of your worries and focus on where you are and how you want to photograph something or someone. I really enjoy finding beauty in things that most people wouldn’t initially identify with or wouldn’t easily connect with. I’ve had people approach me when I’m photographing something ordinary and ask me what I’m taking an image of - and then when they stand with me and I talk them through it, more often than not they will get an appreciation for something that they just were not aware of.

• Platforms, waiting rooms, petrol stations and airports, I sense a recurring transport inspired theme in your work, more than you just travel a lot. What is your photographic relationship with these places?

You’re spot on - I enjoy photographing each of these transitory spaces and I’m certain that my upbringing of regular travel and moving around the world as a child has played a big part in my attraction to these scenes. For me each of them represent memories of going somewhere else, somewhere new to explore, and these scenes represent that feeling of a journey more so than the final destination. They are also places where unlimited stories unfold - as many of us can understand the feeling that is being experienced when looking at the images. There is also the mystery and wonder of thinking about where other people have been and where they are going as they pass through these places of transition. There is also the tinge of loneliness that exists in images that can come from a transitory scene, which can be both beautiful and somewhat sad at the same time.

• For me, your work leans toward documentary but you seem very happy to include people in your frames, in a sort of urban landscape/street photography combination. Do you intentionally overlap genres?

The first thing that I really enjoyed photographing as I got more seriously into photography was street photography in the traditional sense of the word - with the aim of capturing the “decisive moment” that is often understood to be a classic approach to the genre. I followed this approach for quite a few years before felt like I wanted to experiment more with a slower approach to photography. I found that I naturally tended to include fewer people in my images and was more interested in spaces and scenes.

I don’t really tend to think about genres when I’m out shooting, or even when I’m not - it’s more a process of what I feel like photographing at the time, which is driven by a myriad of things. So more of a gut instinct than a decision to have people in an image or not. I think that street photography is a subset of documentary photography. While I think of myself as a documentary photographer, I have also recently become interested in directing my images more in terms of the specific use of people in a given scene of interest - this is something that I’m only just starting to work on at present.

• In your ongoing series American Dreams, there is a definite documentary and topographic feel. This differs with your series The Italian Job where most frames are populated with human figures. How did you decide on this different approach?

I think the difference between those two series can be explained somewhat by the answer above. The Italian Job series was made at the end of 2018, whereas the American Dreams series that has been made so far was shot in early 2020. So I think that towards the end of the Italy trip a lot of my images tended to have fewer people in them, this then continued in the time between my travel to the USA. Another driver of the difference is the fact that a lot of the Italian series was photographed using 35mm - I brought an M6 and Mamiya 7 with me. I find that when I’m shooting 35mm the images tend to be quite different, in terms of content than if I’m photographing in medium format. When I was in the USA, I photographed almost exclusively using either a Mamiya 7 and a Rolleiflex - so medium format. Again this forces you to slow down and changes the way you approach a scene. Lastly I think the areas that I was visiting did impact the final images too, as in Italy I spent some time in the cities, whereas a lot of the images in the USA series were made in rural areas - where there are naturally fewer people.

• Can you explain how you approach a shot, what attracts you to a scene and how you interact with a location?

I tend to do a lot of walking and often find that the vast majority of images I take occur on the journey from one place to another. Sometimes I will hop on the train to a new location and just explore what I find when I get there - it’s the mystery of not knowing what you’re going to find that is part of the enjoyment of photography for me. Other times I will be driving along and see something down a side street that catches my eye and turn off to check it out. There are of course also times where I will see something in a magazine or on the internet that looks interesting, or i’m going on holiday somewhere specific and will plan out heading to a specific location for an image i’ve got in mind. When I approach a shot, very often I will find one angle that is the way that I want to represent a given scene. I tend to find this usually happens quite quickly - as if there is only one way that I can properly connect with something visually. Occasionally a scene or space needs a lot of scouting or walking around to get an angle that I agree with and I’ll take a few different photos to see what works best. There are times when I’m outside shooting and there is changing light - from full sun to clouds. If I want something to be cloudy I’ll happily wait for a few minutes (assuming i’ve got time) until the clouds give me the light that I’m looking for. So really there is a mix of various things going on, but quite often a lot of the images I take are just events that happened to occur during my day whether I’m out with the intention of photographing or not. So as much as possible i’ll try and take a camera with me when I’m out and about.

• You shoot with film, what are the characteristics of analogue photography that appeal you?

There are so many reasons that help to answer this for me. Firstly there is the tangibility of having the photo recorded on a physical negative - I enjoy holding them, scanning them, cutting them into strips, sliding them into the sleeves, writing on the sleeves and filing them away. I’ve always been fascinated about the power of a photography to document something and I think that having a physical record is an important part. Then there is the fact that there is no way of reviewing what you’ve just shot. This means that when you’re out and shooting on film, you get more time to actually focus on being in the moment and I’ve found that it actually makes the experience of shooting much more enjoyable. I honestly believe that shooting film has improved my photography, as instead of going out and shooting 10 similar frames of one scene, you think more about what you’re going to shoot on film and often approach a photograph with more intent - resulting in more keepers (and less photos to review later). Delayed gratification - the joy of scanning and seeing photos that you (forgot that you) shot weeks ago is tangible. Seeing images for the first time a week or sometimes month after they’ve been taken really feel like opening surprise Christmas presents. The limitations of film, from an ISO point of view, force you to be more creative - and so you end up shooting very differently. When I was in Tokyo a few years ago, the quickest film I bought was ISO400. At night in the city, if I’d have been shooting a digital camera I would likely have set the camera at ISO3200 and shot with a high shutter speed. As I only had the film camera with 400 speed film in it, I ended up shooting at shutters of 1/8 or 1/15 resulting in some motion blur and a completely different feel to all of my other daytime images. There is also the ability to continue to use all of the incredible and well made film cameras from decades ago. The lenses and films used give the photos produced a look that can’t be replicated using digital cameras. For my personal work I just prefer to shoot film. Long answer to a short question.

• You appear to favour colour over black & white, can you tell me a bit about why colour works best for you and what is your favourite colour film?

It’s funny, when I started taking photography more seriously a while back I used to convert a lot of my digital images to black and white in post processing. I think i must have thought that “serious” photos were shot in black and white - maybe this came from the fact that traditionally all photography was made in black and white? This was also around the time when I was shooting a fair bit of street photography too. As I started to shoot film more again, initially I shot the majority of it in black and white too - a mixture of Trix & Tmax. Then I started to add in the odd roll of colour film in too. I found that I was getting my scans back, I was really enjoying the native colours in the images a lot - they just seemed a lot more authentic than the colours that I was getting from my digital images. I also found that it somehow gave me more of an appreciation for the colours that I was seeing as I was out photographing too - and I gained an understanding more for colours that worked together in a given scene. There are beautiful colours all around us, and I think the process just enabled me to see this more easily. My favourite colour film is Kodak Portra 400 in 120. I find that it really produces colours the way that I like to represent them and really has great latitude in day and night scenes.

• Who are your photographic influences?

To be honest, it is only recently that I’ve spent some time looking in detail at the work of many other photographers, and while I could name lots, here are 10 of my favourites: Trent Parke, Todd Hido, Mark Power, William Eggleston, Richard Mosse, Stephen Shore, Joel Meyerowitz, Greg Girard, Harry Gruyaert, Gregory Crewdson.

• Is there an area of photography that you would like to explore more in the future?

Yes, I’m keen to explore directing my images a little more to see where that could lead to - including environmental portraits.

• We can’t end this interview without mentioning cars, you shoot a lot of cars. What is it about them that attracts you, is there a profound creative reason or are you just a petrolhead who can’t resist a cool motor?

I do have a serious penchant for photographing cars from bygone eras, although this is getting a bit more under control recently (I think). For me I think it is more than just the interesting scene itself. Older cars again take me back to my memories from childhood when I can remember using a pencil to trace and draw out their shapes from a book that my parents bought me. Endlessly flipping through and sketching all of the cars over and over. There is also the documentary aspect, as older cars genuinely are part of history that need to be preserved as their numbers diminish around us. The older cars also seem to have their own personality - as people have owned and loved (to various extents) these cars for sometimes decades, ageing in parallel with them. Lastly I think that there is also a huge nostalgic factor at play too. I have always loved looking at old photos in general, and it just makes you wonder what life was like. So I guess photographing them is just a way of capturing that feeling.

If you want to see more of Mark's work you can follow him on Instagram at _markforbes_ or on his website at www.markforbes.com.au

© All Rights Reserved | Mark Forbes 2021

Vogue Italia

This series of portraits of Juliette was shot at one of my favourite London locations the Hill Gardens and Pergola in Hampstead. One frame was selected by the picture editors at Vogue Italia for their daily photographic showcase PhotoVogue. I’m always happy to have one of my photos selected by them especially when you see the quality of the other photographers and photography there.

Model : Juliette Koch

Portraits taken with Hasselblad 500c/m on Kodak TMAX 400 & Kodak Portra 800

CONTAX RTS III Review

Review of the legendary CONTAX RTS III &

Zeiss Vario-SonnaR T* ƒ3.4 35-70mm

Following my CONTAX S2 review in July, it got me thinking why I liked using my S2 so much more than my RTS II? After all the RTS II had some great features with its centre weighted meter and aperture priority mode, it was a more relaxed camera than the all manual S2. And yet, I did not use it nearly as much. The more I thought about it, the more I kept coming back to my perceived differences between the RTS II and S2. Yes, of course, at their core was a completely distinct design philosophy, top-line fully-featured vs stripped-down fully-manual. But in practice, the decade or more between them bought them closer together so that an all singing all dancing camera from the early 80s began to feel quite similar to a purist camera of the mid-90s. I started to think that if I was going to own and use two 35mm cameras they should be more distinctive, more different. And so I sold my RTS II and started looking for a good RTS III.

The Real Time System line of cameras was born in 1974 with the original RTS. Contax wanted it to stand out from the mid 70s crowd so they employed Porsche Industrial Design to create the elegant body and slick ergonomics of the new camera. This together with a complete selection of Carl Zeiss lenses made it an instant success and a future classic. In 1982 the RTS II was released, it was more evolution than revolution looking very similar to its predecessors satin black and leather Porsche concept but with a host of additional modern features like Quartz timing and an electromagnetically controlled titanium shutter. By 1990 the RTS III was the last Real Time System camera from CONTAX. It was a clear departure from both its predecessors, being altogether larger and heavier. Once again right up to date for the time it had all the features of any professional camera and some of its own, chief amongst them was the RTV vacuum system, more about that later. The RTS III used for the first time a built-in motor drive, something CONTAX had featured on other models since the 137MD in 1980. Spot-Pre-flash TTL function, integrated diopter, 100% viewfinder, bracketing, multi-metering modes, priority modes and data back that will imprint date and time between frames. It was and still is a very impressive camera for a 30-year old design.

As is often the case there were many RTS III examples for sale on the other side of the world in Japan but with taxes and import duties, the cost of these cameras was in my view not worth the risk. I decided that something closer to home would be better. Fortunately, after only a few days I found a suitable one available in the UK and snapped it up. There is always a risk when buying unseen on an auction site, but with care and common sense good deals are available and the reality is that with rare cameras this is often the only way to find them.

Although the RTS III is a lot bigger than both its predecessors it still retains their familiar look and feel. The original ergonomics have not been compromised, the positions of the controls and dials are in the same places and they all retain the quality precise feel that you would expect from a CONTAX camera. At over a kilo without a lens, this robust camera with its integrated grip is surprisingly well balanced and comfortable to handle. Simple is not a word I would use to describe the RTS III, for a start its got a vacuum ceramic back. A what? Kyocera the Japanese corporation who made CONTAX cameras are amongst other things specialists in ceramics. So they gave it an ultra-smooth ceramic film back that sucks the film flat against itself for super-film-plane-sharpness every time a photo is taken. I’m not convinced it makes much difference but who cares, it’s cool and I like it. Gone is the manual winder of the RTS II and me, forgetting to wind on! replaced by an integrated motor drive that is capable of 5 frames per second. Now, I could foolishly squander an entire roll of film in less than 8 seconds in a glorious hail of 1/8000 click-clack shutter fire. There is no need to only use a centre weighted meter, flick a switch and a true 3mm spot meter is also available. Mirror up, no problem, I can even close the eyepiece with a red-spotted internal curtain to stop stray light getting in that way. It’s got +1 EV or +0.5 EV bracketed exposure, a vertical titanium shutter, built-in dioptric adjustment and a 100% viewfinder with interchangeable focusing screens. Aperture and shutter speed is displayed via an attractive light blue and white LED that works perfectly until you use it on a sunny day when you can’t see anything! Then there is my favourite feature, being able to change films mid-shoot. I shoot both colour and black & white and with my medium format system, the ability to change film backs on a shoot is something I particularly value. Okay, so it’s not quite the same thing but the RTS III automatically winds the film back into the can leaving the film leader sticking out. In this way, it is possible to wind a semi-shot roll back and by taking note of the unfinished rolls last exposed frame number swapping films is practical and possible. A semi-shot roll of film can be reinserted and with the lens cap on, shutter set to maximum speed, aperture set ƒ22 and for extra security, close the eyepiece curtain, you can simply shoot back to the previously noted frame number +1 and that’s it a mid-shoot film change. Brilliant.

Talking of lenses, something I did not mention when I wrote about my CONTAX S2 last year, and because I decided to get a lens specifically for the RTS III it’s worth a mention here. I have three Zeiss lenses already, a Distagon ƒ2.8 28mm wide-angle, a Planar ƒ1.4 50mm standard and a Planar ƒ1.4 85mm for portraits. That's pretty much all my photographic bases covered. The thing is, I don’t really like changing lenses that much during a shoot and I wanted a lens that I could leave on the RTS III most of the time, a kind of catch-all flexible lens. Yes, a zoom! I know, I know it’s heresy going from prime lenses to a lazy zoom. But if you don’t try you will never know.

I decided on a Zeiss Vario-Sonnar T* ƒ3.4 / 35-70mm. Released in 1985 this beautiful Carl Zeiss lens features the usual all-metal body and has a build quality that you would expect from any Zeiss lens. Overall it is a surprisingly small and sleek design, smaller and weighing even less than a Planar 85mm ƒ1.4. With its elegant satin black surfaces and tiny pyramid rubber grips, it has a nicely dampened focusing twist and positive aperture ring. The zooming is via a push-pull zoom action. This action is a first for me, and I like it, the lens gives enough resistance to stop it accidentally moving when focusing. At the extreme 35mm end with a definite twist, the lens slips into macro focus, again another first for me and a world of new creative possibilities getting very close to my subject for the first time.

What are the pictures like? I’m happy, the lens appears as sharp as any of the primes I own. It’s a pleasure to use and its versatility makes it a perfect all-rounder, as good shooting landscapes as portraits, I see it as an excellent travel lens. I love using it at 35mm, a focal distance that seems perfect for the urban landscapes that I like so much. It’s not as fast as my other prime lenses but I try to shoot as much as I can between ƒ5.6 and ƒ8 so it’s fast enough and anyway, that’s where this lens sings. I’m not going to write about bokeh, vignetting, flair or any other technical stuff, there’s plenty of information elsewhere on the web about this and that's because in common with nearly all C/Y mount Zeiss lenses this lens is quite sought after by DSLR users. Digital photographers who fit their cameras with adaptor rings seemingly adore these lenses and so I guess the quality of classic glass is timeless.

The Vario-Sonnar T* ƒ3.4 / 35-70mm is that elusive zoom that is optically as good as a bag full of primes and if I were starting a Zeiss collection, after a Planar 50mm this will be the next lens on my list.

Considering the constraints of my existing Zeiss lenses I wanted a second 35mm SLR that offered a distinct and different photographic experience from my all manual stripped-down S2, something I felt that the RTS II did not. With the RTS III that is exactly what I now have, and a bit like the parent of two siblings each with their own attributes and character they are to me, both exceptional.

CONTAX RTS III SPECIFICATIONS

Type: 35mm metal focal plane shutter auto/manual exposure SLR camera

Lens mount: Contax/Yashica mount

Shutter: Electronic quartz-controlled, vertical-travel metal focal plane shutter

Shutter Speeds: 32 seconds - 1/8000 sec. in auto. 4 seconds to 1/8000 sec. in manual mode

Flash Sync: X setting at 1/250 sec. or slower

Selftimer: Quartz controlled electronic self-timer with either 2 or 10 seconds

Exposure Control: Auto exposure: Aperture priority, Shutter speed priority. Manual, TTL auto flash, Pre-flash TTL

Metering System: ø 3mm spot meter centre of viewfinder and centre weighted average meter

Viewfinder: 100% field of view: 0.74 magnification

Dioptric Adjustment: Internally adjustable +1D to -3D

Depth of Field: Preview button

Dimensions: 156 x 121 x 66mm

Weight: 1150g

Miss Complejo

An Interview with Nadia Bautista

Argentine portrait photographer Nadia Bautista, who goes by the online name Miss Complejo, creates with her work a beautiful mixture of pose and story. Never afraid to stretch her subjects limits, she effortlessly captures their expressive physicality. Photographing face-close, full-body, pairs and groups she makes authentic interpretations that seamlessly merge light and dark into her complementary interiors locations.

• Hi Nadia, can you tell me a little about yourself?

This question is always a difficult one for me as I think the artist and the person shouldn’t be separated; therefore I would like to tell you a mixture of both: my biography as an artist as well as the story of the wandering person I am.

I was interested in art form an early age, I studied drawing and painting, I did artistic skating for several years, clothing design, photography; but I realise that everything I studied were skills to express my interior world. They were a sort of bridge, a connection between my inner word and the world out there. Anything that I wasn’t able to express though my mouth, came out through my hands (drawing), through my body (when I skated) and now it comes out through my eyes (when I photograph). I grew up in a small neighbourhood, which I left, but I miss very much.

Sometimes some places seem quite small as we grow, but we must never forget that the rhythms, the movement with which we grew-up with cannot be changed. I will always be a little slow for the city, I keep stopping to look at plants and dogs, and even when I see them within bars, I can't ignore them. Maybe you're wondering, what does this have to do with your work? And I think all this is what I do when I work: something simple becomes complex and something complex becomes simple.

• Hola Nadia, ¿me cuentas un poco sobre ti?

Esta pregunta siempre me resulta un poco difícil, si bien artista y persona, jamás podrán separarse siempre pienso en si debería contarte una biografía de artista, o una biografía como persona, como humana errante. Haré una mezcla de ambas cosas.

Desde muy chica me vi interesada en el arte, estudie Dibujo y Pintura, hice Patín artístico varios años, Diseño de Indumentaria, Fotografía, pero me doy cuenta que todo lo que estudie simplemente fueron medios. Medios, un puente, un conector entre mi mundo interior y el exterior. Todo lo que no pudiese salir de mi boca, salía por mis manos (dibujando), por mi cuerpo (cuando patinaba) y ahora sale por mis ojos (cuando fotografío). Me críe en un barrio pequeño, del cual me fui pero extraño demasiado.

A veces algunos lugares nos quedan chicos, pero no hay que olvidar nunca que los ritmos, el movimiento con el que crecimos no puede cambiarse. Siempre seré un poco lenta para la ciudad, me sigo deteniendo a mirar las plantas y los perros, y por mas que ahora los veo con rejas, no puedo dejarlos pasar. Quizás usted se pregunte, que tiene que ver esto con su trabajo? Y yo pienso que todo esto, es mi trabajo. Algo simple, volviéndose complejo y algo complejo volviendo simple.

• How and when did you discover photography?

The first time I used a camera was when I was 8 years old, I loved taking pictures on birthdays, and then I was given a 110mm analogue camera. In a playful way, I took it with me to every family event; I never thought that this playful part of my life would be something that I would carry on doing all my life: to have fun watching the world around me.

That camera (which I still have) was, over time, forgotten. When I started university we were asked to present a photo production to show the clothes we made (I studied Clothing Design) and that was when something that had never really disappeared emerged again. Almost angry with my career of designing stupid accessories to put on parts of the body, I decided to strip those bodies. Why did no one ever teach me at university that there is so much variety of bodies? That each of them is a new world to explore? It has taken me down a path of passion that for now, has no end.

• ¿Cómo y cuándo descubriste la fotografía?

Mi primer acercamiento a una cámara fue cuando tenía 8 años, me encantaba sacar fotos en los cumpleaños, entonces me regalaron una cámara analógica 110mm. Casi jugando, la llevaba a cada evento familiar y nunca pensé que esa parte lúdica fuese algo que yo llevaría conmigo toda la vida: la de divertirme observando.

Esa cámara (que aun conservo) quedo olvidada con el tiempo pero cuando empece la Universidad nos pedían que presentáramos producciones de fotos para mostrar las prendas que realizábamos (Estudie Diseño de Indumentaria) y ahí fue cuando volvió a surgir algo que nunca había desaparecido. Casi enojada con mi carrera que estaba pendiente de cada estúpido accesorio que ponía en alguna parte del cuerpo, decidí desnudar esos cuerpos. ¿Porque nunca nadie me enseño en la Universidad que existe tanta variedad de cuerpos? ¿Que cada uno de ellos es un mundo nuevo a explorar? Retome un camino de pasión que nunca termino…por el momento.

• As a portrait photographer what does portraiture mean to you and why do you enjoy photographing people?

Portraying people allows me to meet them, and that, in large part is also to know myself. I think of the portrait as a mirror, and learning to look at oneself. Portraying people ends up being an excuse not only to meet them, but also to be able to observe them and in return observe myself and how I am feeling.

I think I could have been a great psychologist due to the fact that I love to observe people, their expressions, their features, the emotions they experience, their changes, and their transformations. Photographing allows me to be there experiencing all those things for a moment, where time stops.

Portraying people allows me to know other possible realities, none equal to another, all different, all valid. It allows me to change my thinking, because I am nurtured by other visions, other thoughts and emotions. I thank each person who has let me photograph them because without knowing it, they have made me a better person.

• Como fotógrafo de retratos, ¿qué significa el retrato para ti y por qué disfrutas fotografiando personas?

Retratar personas me permite conocerlas, y eso, en gran parte también es conocerme a mi. Pienso en el retrato como un espejo, y en cómo aprender a mirarse a uno mismo. Retratar personas termina siendo una excusa no solo para conocerlas, sino también para poder observarlas, observarme a mi, ver que me devuelven, como me encuentro, como me siento…

Creo que pudiese haber sido una gran psicóloga, por el hecho que me encanta observar personas, sus expresiones, sus facciones, las emociones que experimentan, sus cambios, sus transformaciones…fotografiar me permite acompañar muchas de esas cosas por un momento, donde el tiempo se detiene.

Retratar personas me permite conocer otras realidades posibles, ninguna igual a otra, todas distintas, todas validas. Me permite cambiar mi pensamiento, porque me nutro de otras visiones, de otros pensamientos y emociones. Agradezco a cada persona que me ha dejado fotografiarla porque sin saberlo, me han hecho mejor persona.

• Your photography is immersed in trust and intimacy, how do you work with your subjects to portray this?

Prior to the session I have a talk clarifying everything we will do, as much as possible. I try to get the person to ask all possible questions about me or the session. You have to understand that to be naked in front of a person with a camera is to be vulnerable and that there is a situation of power. There are many people who take advantage of that situation ...

Letting yourself take pictures seems like a good exercise, letting another photographer take pictures naked can be one of the greatest empathy to really understand how vulnerable and fragile one can feel in front of a camera. During the session I try to be as respectful as possible, to chat, to open my world to that person, to understand that if there is not a fusion of ideas in the session I am not interested in that photo. A one-sided view of something seems empty to me. I work with people to feed on them, and the photos are the result of a teamwork. The person I am photographing ends up being more important than my camera. Because if one day, I find this media meaningless, I will turn to another medium, charcoal, clay...

• Tu fotografía está inmersa en la confianza y la intimidad, ¿cómo trabajas con tus sujetos para retratar esto?

Previo a la sesión tengo una charla aclarando todo lo que haremos, lo mas posible. Intento que la persona saque todas las dudas posibles sobre mi o la sesión. Hay que entender que estar desnudo frente a una persona con una cámara, es estar vulnerable y que hay una situación de poder. Hay muchas personas que se aprovechan de esa situación…

Dejarse sacar fotos me parece un buen ejercicio, dejar que otro fotógrafo te saque fotos desnudo puede ser una de las empatías mas grandes para poder realmente entender lo vulnerable y frágil que uno puede sentirse frente a una cámara. Durante la sesión trato de ser lo mas respetuosa posible, de charlar, de abrir mi mundo a esa persona, de entender que si no hay una fusión de ideas en la sesión no me interesa esa foto. Una visión unilateral de algo, me parece vacía. Trabajo con personas para nutrirme de ellas, y las fotos son resultado de un equipo. La persona que estoy fotografiando termina siendo mas importante que mi cámara. Porque si algún día, encuentro este medio sin sentido, recurriré a otro, a una carbonilla, a una arcilla...

• Location does appear to play a very important part of your work? Can you tell me about the relationship between location and portrait and what attracts you to a scene or place?

I have always been interested in architecture and perhaps having studied in a faculty where architecture was also taught I learned that spaces can be people. Or maybe it is because as a child my mother took me with her to work. She cleaned the houses of people with an all together different purchasing power, one that was quite different from ours. The places we went to were always incredible, they were very different places to my home, they were places where I was not allowed to touch anything because I could break it! but I could observe it. Without knowing it, my mother encouraged my capacity as a silent observer, thank you, mum. Sometimes I think that my search for places has to do with recreating all those houses where she worked.

• ¿La ubicación parece jugar una parte muy importante de tu trabajo? ¿Puedes contarme sobre la relación entre ubicación y retrato y lo que te atrae a una escena o lugar?

Siempre me intereso la arquitectura, quizás por haber estudiado en una facultad donde también se encuentra esa carrera, y me enseño que los espacios pueden ser personas… O quizás porque de niña mi mama me llevaba con ella al trabajo, ella limpiaba casas de personas con otro poder adquisitivo, bastante diferente al nuestro. Entonces los lugares a los que íbamos siempre me resultaban increíbles, eran lugares muy distintos a mi casa, eran lugares donde no se me permitía tocar nada porque podía romperlo pero si podía observarlo. Sin saberlo, mi mama fomento mi capacidad de observadora silenciosa (gracias mama). A veces pienso, que mi búsqueda de lugares tiene que ver con poder recrear todas esas casas donde ella trabajo.

• We have known each other for over eight years, I have closely followed your photographic style develop over this time… How would you say it has evolved?

I really appreciate this interview especially knowing that you have supported my work for so many years. If I look back, in the distance, I can see evolution. I think that spending time doing something allows one to generate material that changes, mutates. I'm glad I had perseverance doing this. While I feel that my work continues to maintain the same roots from which it began, I think it has expanded. I have incorporated ideas, premises or in-depth ideals that have opened new doors for me. And this is for people, nothing more, nothing less, meeting people makes me investigate deeper all the time what I do.

• Nos conocemos desde hace más de ocho años, he seguido de cerca el desarrollo de su estilo fotográfico durante este tiempo ... ¿Cómo diría que ha evolucionado?

Agradezco profundamente la entrevista, pero sobre todo tantos años de ese lado, siempre apoyando mi trabajo. Si miro para atrás, a la distancia, puedo ver evolución. Creo que el hecho de dedicarte tiempo haciendo algo permite que uno pueda generar material que cambia, muta. Me alegra haber tenido constancia en esto. Si bien siento que mi trabajo sigue manteniendo las mismas raíces por las cuales empezó, creo que se ha ampliado. He incorporado ideas, premisas o profundizado ideales que me han abierto nuevas puertas. Y esto es por las personas, nada mas ni nada menos, conocer personas hace que indague todo el tiempo mas profundo en lo que hago.

• Can you tell me a bit about your workshops? Do you enjoy teaching and what have you learned doing them?

I love teaching! For everything I studied, I always taught from a very young age, drawing, at the University in the subjects I was studying, now Photography. Teaching is difficult, not because of what one knows, but because on the other side there are open minds that are waiting to absorb information. That information can often be wrong, not because of knowing, but because of the human factor. Teaching is not a simple passage of information, it is to make the other doubt so he never gets tired of searching. It is trying to open all possible windows for light to enter ...

• ¿Puedes contarme un poco sobre tus talleres? ¿Te gusta enseñar y qué has aprendido haciéndolos?

Me encanta enseñar! Por todo lo que estudie, siempre di clases desde muy chica, de dibujo, en la Universidad en las materias que fui cursando, ahora de Fotografia. Enseñar es difícil, no por lo que uno sabe, sino porque del otro lado hay mentes abiertas que están expectantes a absorber información. Y esa información, muchas veces puede ser errada, no por el saber, sino por el factor humano. Enseñar no es un simple pasaje de información, es hacer dudar al otro para que nunca se canse de buscar. Es tratar de abrirle todas las ventanas posibles para que ingrese luz...

• Which photographers and artists have inspired and influenced you?

Pablo Piccaso (“The Weeping Woman” and how a feeling can completely deform a person)

Ernesto Sabato (…talking about darkness, losing sight and going deep into pain)

Pedro Almodovar (claim life)

Nadia Lee (searching of characters, narrative)

Sebastian Cvitanic (obsessing with light above all things, doubting the digital)

My mother (the ability to be reborn)

and Araki (photographing without cameras, learning to look).

• ¿Qué fotógrafos y artistas te han inspirado e influenciado?

Pablo Piccaso (mujer llorando y como un sentimiento puede deformar completamente a una persona)

Ernesto Sabato (hablar de oscuridad, perder la vista, adentrarse hondo en el dolor)

Pedro Almodovar (reivindicar la vida)

Nadia Lee (búsqueda de personajes, narrativa)

Sebastian Cvitanic (obsesionarse con la luz por sobre todas las cosas, poner en duda lo digital) mi madre (la capacidad de renacer), Araki (fotografiar sin cámaras, aprender a mirar).

• What is next for you in 2020?

Expansion.

• ¿Qué sigue para ti en 2020?

Expansión.

• Finally, If you were sent on an all expenses paid photographic assignment anywhere in the world, where and what would you like to photograph?

A very difficult question, lately I am thinking a lot about Latin American countries and everything that connects me to them. Bolivia, Peru, Mexico. What would I photograph? People, no doubt, any possible culture is born from them.

• Finalmente, si le enviaron una asignación fotográfica con todos los gastos pagados a cualquier parte del mundo, ¿dónde y qué le gustaría fotografiar?

Una pregunta muy difícil, últimamente estoy pensando mucho en países latinoamericanos y todo lo que me conecta a ellos. Bolivia, Peru, Mexico. Y que fotografiaría? Personas, sin duda, de allí nace cualquier cultura posible.

If you want to see more of Nadia’s work you can follow her gallery on Instagram at misscomplejo

© All Rights Reserved | Nadia Bautista 2020

Collater.al Magazine

This week Milan based culture magazine Collater.al published an article (in English) in their photographic section based on my series In Animate entitled Tom Sebastiano, il fotografo capace di fermare il tempo

Collater.al cover the best of contemporary creative culture in art, design, music and photography and I’m really pleased to be featured in such a great publication.